In defiance, then, Michelangelo resolved to make the ceiling so magnificent, as it would put to shame the "lower" works of his peers. Furthermore, having just produced the finest sculpture in the history of the world, he considered himself a sculptor, not a painter. To be commissioned to paint (let alone to paint the less important ceiling paintings) was, to him, something of an insult.

Thursday, January 31, 2013

Italian Renaissance (pt. 15)

Wednesday, January 30, 2013

Italian Renaissance (pt. 14)

Medici popularity could only last so long, and the Albizzi were eager to take their place. After Lorenzo de Medici's tyrannical reign, the people of Florence began to tire of this ruling family. The Albizzi saw this as their chance to gain control, and before long they got their wish of domain over Florence. The Medici were exiled after Lorenzo de Medici's death.

For the David, Michelangelo used water to limit the dust around the marble and also to keep himself cool while working. It took the sculptor more than two years to finish this masterpiece, which stands 17 feet today. Notice how David carries his sling over his shoulder and stands upright with determined eyes glaring at his foe—the image of confidence.

The bloody reign of the Albizzi became so bad that the Medici returned from exile nine years later, and the chief political advisor of Florence, Niccolò Machiavelli, was thrown into prison and then exiled, during which time he wrote his famous (or infamous) book The Prince, which marked the beginning of the separation of ethics from politics. Giovanni de Medici became Pope Leo X, and the Medici once again took power in Florence.

Tuesday, January 29, 2013

Italian Renaissance (pt. 13)

Monday, January 28, 2013

Italian Renaissance (pt. 12)

Filippo Brunelleschi is another important name of the Renaissance, though he lived earlier than da Vinci and the printing press (sorry—anachronistic, I know). He considered himself more of a mathematician, architect, and engineer than an artist. Also afraid (like da Vinci) of his ideas being stolen, he wrote all his notes in code.

Sunday, January 27, 2013

Italian Renaissance (pt. 11)

Although Leonardo da Vinci is more famous among us today, it was Sandro Botticelli who was the definitive artist of the Renaissance. His figures moved gracefully in space (like those of the Ancient Greeks), and his themes turned from evangelical and ecclesiastical back to the pagan mythology of Greece and Rome and the celebration of human nature. Primavera is a gorgeous work of his that merely dealt with the concept of "the spring." It was pure fantasy (no Bible stories) inspired by poetry that was not biblical.

Saturday, January 26, 2013

Italian Renaissance (pt. 10)

And this is considered da Vinci's most famous work of art: the Mona Lisa, painted between 1503 and 1506 and actually believed to be unfinished.

This marks the first time we've seen oil paintings in Italy, an influence from Northern Europe. Da Vinci was commissioned to paint this (in other words, someone paid him to make this portrait), but the artist never gave it up. He could not part with it, and he kept it till his death. And the advocates to the theory about da Vinci's homosexuality propose this could be a self-portrait—da Vinci painting himself as a woman. There are several other peculiar things which, added up together, make this quite a unique piece of art. For starters, this is again a portrait of a woman. The Renaissance in particular saw the outbreak of female subjects in paintings—but, still a long way away from the feministic apotheosis of women, women in paintings (for the most part) are shown as submissive wives or pure virgins. The Mona Lisa's hands are folded gently to demonstrate this meek and modest nature. Second to consider: the background. Where is she? Scholars are still unable to identify the backdrop in this painting, which contains mountains, rivers, trees, plains, and other pastoral elements—all combined to form something of a super-landscape…or else maybe a supernatural landscape. It has been suggested—taking into account the almost surreal appearance of the landscape and the dark, twilight lighting which da Vinci used—that the Mona Lisa is in Hell. …Let's hope not!

By far the most famous feature of the painting, as you all know, are the eyes (which, by the way, aren't topped by any eyebrows). The eyes, remember, are "the windows to the soul." The Mona Lisa's pupils are so positioned at an angle—again, da Vinci, the scientist—that she appears to be staring right at you. This conflicts with what I said earlier about her submissiveness—a humble woman would look downwards. The Mona Lisa is looking straight at you. …Eh, makes some people feel uncomfortable; like, she's looking right at me—ah! What's more, she has a tiny smirk on her lips as if she's laughing inside. Maybe she knows a secret. Haha, or maybe people just like to make up conspiracies that she does to keep us interested—like the theory that there are microscopic numbers and symbols engraved by da Vinci on the Mona Lisa's eyes (…and, by the way guys, there's a treasure map on the back of the Declaration of Independence, too).

The art elements which da Vinci utilized were revolutionary, and this would have been one of the most realistic-looking portraits of the day. The detail put into her robe and sleeves alone is extraordinary. Add to this that the actual painting was famously stolen and, later on, that a famous artist drew a moustache on a copy and submitted it to an art exhibition, and the painting's fame only increases, this small 30" x 21" portrait of an unknown person in an unknown location. Still a magnificent painting, though (famous or not famous), isn't it?

Friday, January 25, 2013

Italian Renaissance (pt. 9)

Now, I don't know if any of you have read Dan Brown's book The Da Vinci Code or have seen the Ron Howard film, but this was a topic we had to (for some unfathomable reason) study in my class, and so I could say far more about da Vinci, The Last Supper, and several other things, but it would doubtless bore you (it even bores me at times). Besides, I don't think many people buy into the kooky theories presented in the story. Brown himself only intended to write an entertaining fiction. All I'm saying is: I still have a copy of my exhaustive, some fifteen-page essay disproving each of Brown's fictional theories, and I can dish it out if anybody so even thinks those theories hold any credibility! But I spare you of this (heehee)…

Thursday, January 24, 2013

Italian Renaissance (pt. 8)

One of da Vinci's most famous images is that of the Last Supper, a fresco painted on a wall in a monastery in Milan, Italy. The fresco began flaking off almost immediately after the paint was applied because da Vinci the scientist experimented with egg tempera (which did not mix well with plaster), and this is why it is in such poor condition today.

It utilizes one-point linear perspective (as we discussed earlier with Masaccio); this time Christ is the center of the composition. It is, rather than really telling a story (like the storytelling murals of the Medieval Period), capturing a moment in time. The fresco is of the moment when Jesus announces that Judas will betray Him. Our Lord is calm and silent while the others are in an uproar. The apostles all express disbelief, except for Judas (third from Christ's right), who instead shows a look of anger and defiance—his is the only face in shadow. The twelve apostles all stand in groups of three, and they are all jammed on one side of the table for dramatic appearance—certainly not biblically accurate.

Wednesday, January 23, 2013

Italian Renaissance (pt. 7)

Da Vinci's sketch of the Vitruvian Man shows the proportions of the human body: that each separate part was a simple fraction of the whole. For instance, the head measured from the forehead to the chin was exactly one tenth the total height. The outstretched arms were always as wide as the body was tall. (It's a generally applicable rule that your arm-span matches your height—go ahead and test it out).

Vitruvian Man was named for Vitruvius, a mathematician that practiced mathematical ideas for Pythagoras. In this drawing, da Vinci tests Vitruvius's theory that a man's proportions would fit evenly in both a square and a circle (the spiritual realm and physical realm).

Tuesday, January 22, 2013

Italian Renaissance (pt. 6)

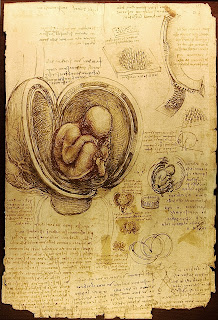

Da Vinci dissected cadavers to study the human body's inner workings. This was illegal at that time, so the scientist had to work in dark, secret places. (For the most part his subjects were bodies of people who had been hanged.) These drawings contributed greatly to modern science. Historians believe the Egyptian priest Imhotep may have actually made similar anatomical notations thousands of years earlier, but his notes are lost, buried with him in his unknown tomb. So, for all intents and purposes, da Vinci is the first great anatomist. Of course he's also been accused of being a homosexual for a few reasons, one being that he made several drawings of female sexual organs but none of male sexual organs.

Because of all the pains he went to to study the human body first-hand, da Vinci's were considered the most realistic human depictions to date.

Monday, January 21, 2013

Italian Renaissance (pt. 5)

The Renaissance marks the beginning of modern science in Europe. Some of the most significant contributions to science at the time were made by the scientist Leonardo da Vinci (who, by the way, considered himself a scientist, not an artist). Leonardo da Vinci is considered one of history's most fascinating characters to study. Most of da Vinci's works were produced around 1500. Da Vinci's notebooks included everything from plans for flying machines to weapons to human anatomy to botanical drawings. He wrote everything in his notebooks backwards, out of paranoia that someone would steal his notebook and ideas.

Sunday, January 20, 2013

Italian Renaissance (pt. 4)

This is a fresco by Masaccio (an important Renaissance artist) of the Holy Trinity. It is a landmark work of art, considered the first successful illusion of one-point perspective. It ignored detail and focused on the realistic qualities of mass and depth. It shows Christ (the Son) on the cross with the Father behind. The Trinity is made complete with the presence of the Holy Spirit. (Can you find Him?) Masaccio went with the idea that the Holy Spirit took the form of a dove (as with our Lord's baptism), and so the Holy Spirit is the little white dove that actually looks like God the Father's neck collar. The people on the left and right are the patrons who commissioned the work (their placement at the foot of the cross would demonstrate their devoutness—and by having a massive fresco painted of them it actually was sending the message of how humble they were…yeah, got that).

Shortly after Masaccio's Holy Trinity, Brunelleschi developed his theory of Linear Perspective—a geometric method of representing the way that objects appear to get smaller and closer together the farther away they are. The first book to include a treatise on Perspective was published in 1436.

One-point perspective will dominate art until we get to Impressionism. To mimic a 3-dimensional environment it contains a vanishing point, which is the point (often invisible) where the floor touches the sky—the horizon line, basically. One-point perspective, naturally, contains one vanishing point (the meeting point of all angles). Arguably the most definitive painting of one-point perspective was painted during the Renaissance, to be found on a wall in the Sistine Chapel in Vatican City.

Saturday, January 19, 2013

Italian Renaissance (pt. 3)

During the Renaissance, Italy was a collection of city-states, each with its own ruler—the Pope in Rome, the Medici in Florence, the Doge in Venice, the Sforza in Milan, and the Este in Ferrera. Among the ruling families of these city-states there was unceasing conflict and intense rivalry, either by open warfare or, in times of peace, through economic and artistic competition to achieve the most brilliant court. The Republic of Florence (Firenze) was the richest of them all and even the richest in all of Europe because of its successful cloth trade and because the richest banking house operated there. The Medici family, therefore, consisted of arguably the most powerful people in all of Europe at that time, rivaled by the Albizzi, who constantly contended with the Medici for power.

There is a very good PBS documentary called The Medici: Godfathers of the Renaissance, from which you can learn a lot more about the ruling family of Florence—and the narrator's voice in it is hilarious. Basically, the Medici are all over this time period. They started from humble beginnings, however; they started out primarily as working-class bankers and moved up to power. And you'll see the extent to the Italian phrase amici del amici ("friends of friends"). Brunelleschi, friends with Donatello, was the house architect for the Medici, and Leonardo da Vinci was apprentice to Lorenzo de Medici—just to name a few names. The Medici were generally the ones who commissioned the great artists to produce their masterpieces (and add in propaganda images to promote the Medici and Florence—Benozzo Gozzoli's fresco The Procession of the Magi is the prime example of this, sending the message of Medici supremacy).

Friday, January 18, 2013

Italian Renaissance (pt. 2)

Although there is no set date for the beginning of the Renaissance—like in 1401 everybody referred to things of the previous year as "so Medieval!"…nuh uh—I'd place it close after the perfection of the printing press by Johannes Gutenberg in the mid 15th century, which made books widely available. It was the invention of a millennium.

The painter who made much of the transition from old to new possible was Fra Angelico. Here is his Annunciation fresco (the Annunciation is the moment when the archangel tells Mary she is to give birth to God's Son).

We see characters moving in space again, and the space is defined using linear perspective (which I'll get to in just a moment). Notice the columns? The front ones are Corinthian and the ones on the left are Ionic. This is the just the beginning of what will be the return to Greco-Roman ideas and art styles.

Thursday, January 17, 2013

Italian Renaissance (pt. 1)

Some considered the grandiosity of art as a show of pride, that only stuck-up, self-absorbed, narcissistic men could paint such extravagant and beautiful paintings. If the plain art of the Byzantine Empire carried the connotation of humility before God, art of the Renaissance sent the opposite message. This was an elevation and celebration of humanity, of genuine human expression and artistic talent.

Wednesday, January 16, 2013

The Gothic Period (pt. 3)

Of course you all know about the horrendous Black Plague that caused a devastating number of casualties all throughout Europe. This understandably put a halt on very much progress, and the recovery phase after this catastrophe took a while. Then, in the following century, we see the invention of the printing press and arrive at the Renaissance, so get ready to party.

Tuesday, January 15, 2013

The Gothic Period (pt. 2)

Stained-glass windows become very popular. This would have added to the already dramatic lighting found in churches (like Hagia Sophia). Remember that light is a symbol of God's presence. What better art could have been made at this time than art which could literally light up in the sun and radiate its colorful splendor in the church.

Another element added to churches was flying buttresses, which is a hilarious name for the supporting columns on the outside of the main infrastructure. Quasimodo slides down Notre Dame's flying buttresses in the Disney version of Hugo's The Hunchback of Notre Dame.

Monday, January 14, 2013

The Gothic Period (pt. 1)

The Romanesque Period fades into the Gothic Period, which started in France. The main elements of Gothic style are architectural.

Sunday, January 13, 2013

Romanesque Medieval (pt. 6)

Notice a trend here? Art during this time is almost solely purposed towards religious, evangelistic, and ecclesiastical ends. Romanesque painters had the ability to be realistic in their art (that is, they had the skill to create graceful and beautiful figures like those of the Greeks), but they chose not to be. They wanted to make their stories simple and straightforward without too much artistry so that people could easily understand the biblical lessons presented and get saved.

Saturday, January 12, 2013

Romanesque Medieval (pt. 5)

Columns also provided a place to add artwork to. The column capitals became a prime spot for reliefs of more stories, but the storytelling on these was often strange. For instance, a story is shown of a cat feigning death and being carried off by mice only before springing back to action and defeating the mice (kinda random). This could be a proverb to represent the return of Christ, or it could just be Medieval humor.

Paintings were made on church walls, too. At San Clemente in Tahull, Spain, a painting of Christ is drawn in a sphere, representing the universe that He controls. It uses patterns and bold colors to emphasize its effect.

Friday, January 11, 2013

Romanesque Medieval (pt. 4)

God the Father is the large figure appropriately located in the center (hierarchic scaling). On His right side are the believers to whom the Kingdom is promised, while on His left are the condemned. The twelve disciples stand below God. …Why put a huge carving of the Last Judgment right above your church doors? This image, and the idea of judgment of sinners, was meant to scare people into church. Theoretically, this warning would terrify people so much that they would run into the church for salvation. …And then the priests would make more money.

Thursday, January 10, 2013

Romanesque Medieval (pt. 3)

In the center of each town was a church. Religion became an essential part of everyday living. Churches' lavish decorations and designs were a testimony to the institution's power. Pilgrimages became a common phenomenon—these were journeys to a holy place, usually done to pay homage to saints and relics in far-off churches.

The church design remained the same as it had been. A transept, which was another aisle that cut directly across the nave and side aisles, was in common use by now, and ambulatories were added (an aisle curving around behind the main altar). You'll note that the plan of a Romanesque church looks like a cross from a bird's eye view (or, perhaps, from a "heavenly" perspective).

The church of Saint Sernin, in Toulouse, France, is typical of the Romanesque style. Its exterior is large and solid, a real "fortress of the Lord," and its interior is spacious, with dark lighting and a gloomy atmosphere meant to produce penitence in the hearts of visiting sinners.

Wednesday, January 9, 2013

Romanesque Medieval (pt. 2)

Castles were primarily built for defense—not pleasant places to live in. Fireplaces were the only source of heat. Stairways were extremely narrow, a claustrophobic's worst nightmare. Contrary to what the highly romanticized Disney films would tell us, castles were uncomfortable and uninviting places to stay in. Virtually the only color in these stone dwellings were tapestries, which were textile wall hangings that were woven, painted, or embroidered with colorful scenes. One such famous tapestry is that of the Battle of Hastings, from England.

Even though these town walls proved successful in guarding from intruders, it also led to overcrowding as more people inhabited the towns. The walls literally set a limit on expansion. To solve this problem, architects built upward and added on to the buildings' height, making the streets below darker. (Interesting…)

Tuesday, January 8, 2013

Romanesque Medieval (pt. 1)

Now we come to the Romanesque Period, which is the time of Robin Hood, Maid Marion, Friar Tuck, Little John, Allen a Dale…and—who could forget?—Will Scarlett. Anyway, the Romanesque Period becomes fully developed in Europe by the 11th century. There is more art during this time than in the Early Medieval Period.

Feudalism reached its peak in the Romanesque Period; it was the cause of a lot of the unrest during Medieval times. Land was the source of power and wealth, so naturally the fighting and wars were over land. To defend the valuable land which you had already, it was necessary to construct stone fortifications, or castles, which featured towers, walls, moats, and drawbridges (among other architectural elements). No other creation defines the period so well—castles are the quintessential Romanesque symbol.

Monday, January 7, 2013

Early Christian Art (pt. 13)

Giotto's Pietà is a fresco, which is a painting created when pigment is applied to a wall spread with fresh plaster. The fresco had to be completed before the plaster dried. If there was a mistake, the whole thing had to be redone. Because it dried so fast, it had to be done quickly, and there wasn't always time to add everything. Fresco means "fresh."

Sunday, January 6, 2013

Early Christian Art (pt. 12)

Notice all the gold; this is typical Byzantine style, along with the intense colors, 2-dimensional figures, and shallow space (by shallow space I mean: look how crowded everyone is up there). However, this altarpiece is more realistic and solid and not as stiff as some other examples of art during this time. There appear to be emotions on the figures' faces, making them slightly "more human and less holy."

Saturday, January 5, 2013

Early Christian Art (pt. 11)

Justinian was the Byzantine Emperor from 527 to his death in 565. Wanting to be like the early Roman emperors, he decided to build a great church in Ravenna that would be the greatest in the world. The church, San Vitale, became the most important church in that time period. Inside San Vitale, artisans made two mosaics (among others); they are breath-taking. One shows the Emperor with the archbishop, deacons, soldiers, and attendants. The bodies of the more important people overlap those of lesser ones, but the archbishop's leg is in front of a part of Justinian's cloak, symbolizing that the church was supreme.

On the other wall of San Vitale, facing Justinian and his attendants, is Justinian's wife, the empress Theodora, and her attendants. The empress is dressed in magnificent robes and wears the imperial crown. She is shown to be equal to any saint in Heaven and also wears a halo.

The figures seem to float in space before a gold background (used to add a supernatural, heavenly glow to the scene). A feeling of weightlessness is heightened by the lack of shadows and by the position of the feet, which all hang downward limply as if they really were suspended in the air. But, if you ask me, most striking of these mosaics are the eyes. Deep, penetrating eyes they are, n'est-ce pas?

Friday, January 4, 2013

Early Christian Art (pt. 10)

…Eh, so this is all labeled "Christian art," but there's a mighty great number of Virgin Mary's here, and it'll stay this way for pretty much the rest of history (everything is "Madonna with Child," etc.). These churches were labeled "Christian" churches, but this was the time of the Holy Roman Empire…which is Catholic. And naturally, a Christian is a follower of Christ, is somebody who has turned his/her life over to Christ, trusting in Him for forgiveness from sins and the hope of Heaven…but historians use the term "Christian" usually to just describe a sect of people, like the ethnicity of the Western, church-going folk. The textbook connotation of a "Christian" is very poor, but this is textbook semantics—don't get me started! So, when I say that these are "Christian" churches, built by "Christians," in the "Early Christian" era…you know what I'm talking about (wink, wink). I should say Catholic, because that's more or less what it is, but that could become confusing, since the name given for it is Christian. Christians (in the true sense of the word) believe that Jesus Christ is the Son of God and the only way to salvation and atonement with God. So I have no idea why the Virgin Mary, a very human being, is inserted EVERYWHERE like she was equal or even better than God's own Son, but then again there are a lot of Catholic doctrines I don't get, so nothing new under the sun…

Thursday, January 3, 2013

Early Christian Art (pt. 9)

The mosaics inside Hagia Sophia caught the light and would shimmer, making for even more dramatic lighting to emphasize the message of God's greatness. The mosaics had to be large and clearly visible, as well as brightly colored, and they had to be recognizable Bible stories. As stated before, the Byzantine artists' intention was to glorify Christianity (actually, it's very Catholic, but I'll get to that later); their works are flat, stiff, and unrealistic because it was necessary to portray clear and simple religious lessons to the illiterate. They did not aspire to create beautiful and graceful figures like the Greeks. Their pictures were meant to be humble, paying homage to God for salvation, and clearly presenting the Gospel message without giving any attention to superfluous and irrelevant aesthetic elements.

Wednesday, January 2, 2013

Early Christian Art (pt. 8)

As for the Byzantine Empire, they quickly grew in wealth and predominance. Some say they were only a continuation of the Roman Empire since they were the Eastern half of the earlier Empire that continued after the schism; however, the differences are notable. Byzantine art took to glorifying Christianity and serving the needs of the church (not a very Roman ideal). During this time, in fact, the church probably had the most power of anyone. As Christianity became more popular under Constantine, it became necessary to build more churches. Byzantine architecture preferred a central plan to the Roman basilica model, and it utilized piers (massive vertical pillars).

Byzantine builders also made their churches to be "Houses of Mystery" with dramatic lighting, mosaics, and an overall dreamlike setting.

The walls of Hagia Sophia are thin with more windows to make for a more luminous interior. The streaming light from all the numerous windows acted as symbolism for the church-goers, who recognized that Jesus is the light of the world. From here on, light is almost always a symbol of God's presence, and it comes from the lighting in Early Medieval churches.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)