I mentioned earlier there was widespread church construction occurring at this time. Christians borrowed from Roman basilica designs to create their churches, designed to fit a large number of church-goers. A Campanile (a freestanding bell tower) and Westworks (towers framing the end of a church) were added to the design. Exteriors were plain (contrary to when we get to Gothic architecture), and the focus on these early Christian churches was the interior. Interiors were designed for dramatic effect, to bring a sense of awe to worshippers—in fact, a nickname for churches built at this time was "Houses of Mystery." The church builders put in mosaics, which were decorations made with small pieces of glass and stone set in cement. The mosaics themselves were like visual sermons, complete with symbols for Christ's majesty and goodness, for viewers to admire when they were not looking at the priest. Many of the mosaics were placed next to flickering candles, the light of which would cause them to glow. "Houses of Mystery."

Wednesday, December 28, 2011

Sunday, December 18, 2011

Early Christian Art (pt. 6)

Monasticism was a way of life in which individuals gathered together to spend their days in prayer and self-denial. Monks were common during the Medieval Period. They separated themselves from the warfare and chaos around them to devote their lives to holiness. They built monasteries like this Monastery of San Juan de la Peña in northern Spain, deep in the forests covering the foothills of the Pyrenees and tucked away from the rest of the world.

It was built right into the cliff side. The outside looked like a fortress, and the inside was mostly dark and only lit by torches. There was an upper story that opened to a cloister (an open court or garden surrounded by a walkway) next to the cliff overhead.

In these monasteries, the primary activity of monks was copying ancient texts (usually the Bible). These had to be done by hand, since this is before the printing press. The monks wrote their books in Latin. Along with hand-copied books, manuscript illuminations became the most important paintings in Europe for a thousand years. They are the most classic example of Early Medieval art. Manuscripts were decorated with gold and silver leaf, and for those who could not read the text (since, as I mentioned earlier, literacy was quite low), illustrations were put in. A typical example of an illuminated manuscript looks something like this.

Thursday, December 15, 2011

Early Christian Art (pt. 5)

One of the reasons why the Early Medieval Period was so "dark" is that literacy was at an all-time low. The average number of books to be found in a Medieval library was twenty. However, during this time we see a brief glimpse of advancement. The Carolingian dynasty emerged but only survived less than 150 years. It was responsible for efficient government and renewed interest in learning and the arts. Charles the Great (Charlemagne) was the best of the Carolingian dynasty. He was King of the Franks and then elevated to the papacy on Christmas Day in the year 800 and then made the first Holy Roman Emperor. His domain included almost all of the Western half of the old Roman Empire, and he tried to rebuild the splendors of Rome, starting at his capital, Aix-la-Chapelle in Germany. Much like the Romans who imported Greek artists, Charlemagne brought in scholars from other countries to teach in the new schools he was constructing. Learning and the arts sparked to life, but then Charlemagne died in 814, and the strong, central government collapsed again, sending Europe back into feudalism.

Here is a small statue that was made at the time. It depicts the great Holy Roman Emperor, crowned, riding on a horse. Notice what he's carrying in his hand?

Tuesday, December 6, 2011

Early Christian Art (pt. 4)

In the 4th century A.D., Rome was on its way to total disillusionment. The Eastern Empire became the Byzantine Empire, with Constantinople for its capital. The West fell to barbarian invasion, and the emperors lost their power. The fall of the leaders in the West led to the rise of the church, and in the West we see widespread construction of churches in this area during the Early Medieval Period. (I'll get to the churches in a bit…)

The Medieval timeline is split into three parts: (1) Early Medieval, (2) Romanesque, and (3) Gothic. The Early Medieval Period starts with the fall of Rome. Strong, central government is gone; the ruling influence during this time is uncertainty, conflicts, open warfare, and apparent chaos. Feudalism is pretty much the only system of order, and it entails a system in which weak noblemen gave up their lands and much of their freedom to more powerful lords in return from protection. Serfs were the poor peasants who had no land.

Wednesday, November 30, 2011

Early Christian Art (pt. 3)

These murals are what are considered Early Christian art, though in actuality it is far more than just art. Christian art was intended to illustrate the power and glory of Christ; beauty or aesthetic principles were of no concern. The images are symbols, almost like a form of code, since the Christians were in hiding from the Romans. In fact, the official strategy was to use Roman symbols to tell Christian stories. So we see images of animals, birds, and plants—for example, a goldfinch. Goldfinches appeared in Roman art as merely a bird; however, it was a known fact that goldfinches ate thistles and thorns, and so to the Christians, the bird was a reminder of Jesus' crown of thorns. Other such symbols were dogs (to represent loyalty) and ivy (to represent eternal life). Here is a mural from a catacomb: an image of a shepherd feeding his sheep. To Roman guards, the image is harmless, but Christians remembered Jesus' words that He is the good shepherd, and that He lays His life down for His sheep (John 10:11).

Thursday, November 3, 2011

Early Christian Art (pt. 2)

"Et tu, Brutè? —Then fall Caesar." Shakespeare penned this famous line as the dying words of the great Julius Caesar, and if you're more interested in Roman culture, government, and history—or if you just enjoy excellent poetry—I highly recommend the play. Julius Caesar was murdered by the famous group of conspirators (including Cassius and Brutus) on March 15, 44B.C. He was stabbed 23 times in a back room of Pompey's Theater in Rome. Octavian became the next Caesar and eventually changed his name to Augustus Caesar (which meant "exalted one"). Remember, he was the statue with Cupid clinging to his robe. He claimed divine right kingship, but only after having achieved the throne with the help of the murdered Julius Caesar's will. Augustus ruled until 14A.D., after which time Tiberius, Augustus' adopted son and heir, took the throne, as Luke records in his Gospel.

The Romans occupied Palestine at this time. You will remember that the Roman Empire was so vast that it had long since become necessary to administer rulers for the different regions. The Roman Senate, with Augustus Caesar's and Mark Antony's support, elected Herod (known today as Herod I or Herod the Great) to be King of the Jews in Palestine. His reign as such lasted from 37B.C. to 4B.C.

Approximately 6B.C., Jesus is born in Bethlehem, Israel, and Herod the Great tries to kill Him. Jesus and His family escape to Egypt until Herod dies from a terrible illness in 4B.C. After Herod the Great's death, Palestinian rule was divided among his three sons: Archelaus, Philip (Philip II, known as the Philip the Tetrarch), and Antipas. Herod Archelaus was quickly removed from office by the Roman authorities and replaced by Pontius Pilate. Herod Antipas is the man who married Herodius, his brother's wife. (The brother was Philip I, not to be confused with Philip II, the Tetrarch). John the Baptist confronted Herod Antipas on this wrongful act, and Antipas had John executed. Antipas is also the Herod who questioned Christ on the night before His crucifixion in 30A.D.

Tuesday, November 1, 2011

Early Christian Art (pt. 1)

Now, we have looked at Roman art as it was seen above; but, as you know, there was another world underneath Rome during the Empire. This is called Early Christian art.

Friday, October 28, 2011

Ancient Rome (pt. 7)

So, how did one of the greatest empires in history collapse? Eventually, as they accumulated more territory, the Roman Empire became too large to keep under a single Caesar's control. The Empire was divided into a tetrarchy (rule by 4), which was the first step to a divided empire. Diocletian (one of the Caesars) was the one who issued this tetrarchy into order. Then, in 305A.D., after suffering from illness the year before, Diocletian did the unthinkable and became the first Caesar to retire from office. This shocking abdication of power further divided Rome. As fighting broke out, another controversial move was made by the Roman leaders: the capital was changed from Rome to the ancient Greek city of Byzantium (later called Constantinople, after Constantine). An ensuing schism eventually ended the Roman Empire, splitting it into Byzantine East and Latin West. During the long struggle with invaders from the north, cities in the Western Roman Empire were abandoned by frightened inhabitants who sought refuge in the countryside. The population dwindled from 1.5 million to about 300,000. Magnificent temples, palaces, and amphitheaters were torn down, and the stone, marble, and concrete was used to erect fortifications to keep the invaders out. The effort was useless. Once-proud cities were overrun, and their art treasures, destroyed or carried off. Following this is the Dark Ages.

Tuesday, October 25, 2011

Ancient Rome (pt. 6)

The Colosseum was a huge arena built for gladiator tournaments. It is a great example of how Roman architects took from previous Greek ideas and made them their own. Notice the half-columns on the outside. The bottom row is the Doric Greek Classical Order; the second row, Ionic; and the third, Corinthian.

Once again, this gigantic structure was made possible via light, quick, inexpensive concrete. Why is the Colosseum in such poor condition today? Over the centuries, different rulers took parts of the Colosseum for various things. The extra concrete came in handy particularly during the chaotic Medieval period, when castles were being erected fast and with those materials that were easiest to find.

As you can see, there is very little religion pictured here. These monumental infrastructures were not built for the gods but for the people themselves, and (more often than not) merely for their own entertainment. Theaters, amphitheaters, and stadiums like the Circus Maximus were all constructed for the entertainment of the masses. Fascinating sociological implications here. We know that the culture was steeped heavily in debauchery, violent spectacles, and homosexuality. They are infamous for their persecution of Christians, more of which I'll get to up ahead…

Sunday, October 23, 2011

Ancient Rome (pt. 5)

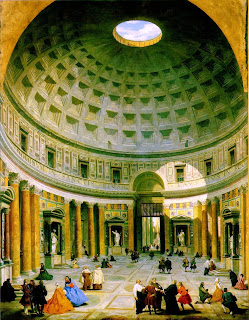

The Pantheon, which was a temple built for all of the gods, was the first large dome.

Concrete allowed the Romans to construct large-scale buildings. Many of the famous Roman monuments still stand today. Because the empire covered such a wide territory, their building skills covered a large area too and were very big. (Hence, the Romans are considered to be the "great builders of the world").

Baths were vast enclosed structures that contained libraries, lecture rooms, gymnasiums, shops, restaurants, and pleasant walkways. They had rooms with progressively cooler water: a Calidarium, a Tepidarium, and a Frigidarium. The largest Bath in Rome was built by Caracalla; the vaulted ceilings were up to 140 feet high.

Thursday, October 20, 2011

Ancient Rome (pt. 4)

The basic architectural style stayed the same (pediment, entablature, columns, and 3-tiered platform), but the Romans added more stairs that only went up to the front of the building, whereas Greek temples had stairs around every side. Half columns were a new feature, also; these were attached to the solid walls to create a decorative pattern. Basilicas featured a nave (long, wide, central aisle) and an apse (semicircular area at the end of the nave). (More on this when we get to the Medieval era…)

Examples of Ancient Roman architecture are: baths, amphitheaters, theaters, triumphal arches and bridges, the Colosseum, and the Pantheon—among many others. Another huge innovation at this time was the Roman aqueduct, which was a system that carried water from mountain streams into cities by using gravitational flow.

Tuesday, October 18, 2011

Ancient Rome (pt. 3)

A staple of Ancient Roman artwork is murals, which are large pictures painted directly on walls. These walls were the interior walls of private civilian homes, and the murals were generally of landscapes or buildings. The paintings made it look as if the wall was a window into another place. Although many of them are plain, simple household images, the art element introduced here will later become known as trompe l'œil, which is French for ("fooling the eye"). The images were meant to look three-dimensional and totally real as if the mural really were a window showing viewers actual objects on the other end. Here is a mural of some peaches with a vase of water. Notice the light reflecting off the water vase? So realistic!

The city layout during Ancient Rome is what we still follow today—parallel and perpendicular streets, facing North-South (cardo, the Romans called these), or East-West (decumanus). The place of meeting (called a forum) would be located on the intersection. A typical forum included shops as well as the primary religious and civic buildings—Senate house, records office, and a basilica.

Sunday, October 16, 2011

Ancient Rome (pt. 2)

Ancient Roman art is another story. The Romans were obsessed with Greek art, and they copied the style whenever they could. They purchased artwork from Greece and even imported many Greek artists. This is why there is so much Greek influence seen in Roman art and architecture. The original statues made by Greek sculptors like Polyclitus and Myron have been lost; and the ones we have today are Roman copies (of which there are many). In fact, it could be said that Roman art was merely a copy of Greek art, but for a few changes.

The Romans, like the Greeks, loved idealized bodies of young athletes to show power and domination; however, they believed that a person's true character was to be seen in the person's face. And as Greek artists had to satisfy the tastes of their patrons, the result was young athletic bodies with old heads.

Eventually, the Romans realized that it was cheaper just to make busts (head portraits) instead of whole body portraits. Since they cared so much about faces, many busts appear during this time. And not all of these were public works of art. Sometimes a bust was made for the private purpose of remembering a deceased loved one in a particular family. The Romans introduced "death masks" at this time, which were busts cast from an imprint of the actual head of a corpse, giving the exact image of the deceased's face. Realism enters the scene, as people want to remember the images of others as how they really looked, wrinkles and all. Where the Greeks tried to exaggerate the human physique tout entier, the Romans focused on specific traits unique to each person. The art had become realistic, lifelike, and personal.

Saturday, October 15, 2011

Ancient Rome (pt. 1)

By 300B.C., the Roman Empire had control over most of the Italian peninsula, and it eventually became the largest empire in history. In 200A.D., the Roman sphere of influence included basically all of Europe, an enormous chunk of the Middle East, and a vast strip of Northern Africa. For all intents and purposes, this is arguably the grandest civilization the world has ever known.

Saturday, October 8, 2011

Ancient Greece (pt. 13)

I don't mind thinking of Minoa as the historical equivalent to Atlantis, but I'm no scholar and am probably good with it just because I've always been fascinated with the myth ever since my imagination was sparked reading The Magician's Nephew, C. S. Lewis's epic fantasy, in which the character Uncle Andrew explains the following to his nephew in the second chapter:

"Ah—that was a great day when I at last found out the truth. The box was Atlantean; it came from the lost island of Atlantis. That meant that it was centuries older than any of the stone-age things they dig up in Europe. And it wasn't a rough, crude thing like them either. For in the very dawn of time Atlantis was already a great city with palaces and temples and learned men."

Not too accurate, but then again the myth of Atlantis is such that gets fantasized all the time. It is almost like El Dorado, or Mars, or the Garden of Eden itself—everybody has their own opinions about its history, about what it could have been like. And it is fun to make up stories about it, like Lewis did. Even Tolkien (a close friend of Lewis's) made a fantasy version of the Atlantian myth to put in his own stories of Middle Earth (the island of Numenor shares several characteristics of Atlantis). Lewis actually wrote a lot about Atlantis. (I know we're way off topic, but I'm there now, so I'm just gonna keep going). He always referred to it as a "mythology," however, not a historical fact or even a possibility. An entry in his diary from 1922 tells of a conversation he had with a friend of his, Dr. John Askins ("the Doc"):

"He talked about Atlantis, on which there is apparently a plentiful philosophical literature: nobody seems to realise that a Platonic myth is fiction, not legend, and therefore no base for speculation."

Friday, October 7, 2011

Ancient Greece (pt. 12)

It's evident that the Minoans were a highly advanced civilization. So, what happened to them?

The evidence shows us that the entire civilization came to a sudden end around the 15th century B.C. (The Exodus from Egypt is dated around this time). Scholars disagree over whether the Minoans were destroyed by a volcano eruption (the nearby Santorini volcano) or tidal wave, or a combination of the two. Both the tidal wave and volcanic eruption were probably caused by a massive earthquake that is said to have taken place around that time. Whatever it was, it was a natural disaster of apocalyptic proportions that wiped the Minoans off the map, although it may not have been altogether instantaneous, as some historians believe. Sources for information are scarce, but one History Channel documentary on the subject claimed some Minoan survivors may have had time to flee north, and that there was some proof of Minoan presence found either in the Aegean Islands or southern Greece (I honestly forget which). For you conspiracy theorists, they say the Minoan survivors birthed a long line of other highly intelligent and advanced people: Leonardo da Vinci, Sir Isaac Newton, and Albert Einstein being among some of their alleged descendants.

Now, also take the two characteristics of this civilization—their advanced innovations and their sudden demise—and some scholars claim the Minoan civilization may be the factual, historical version of the mythical Atlantis. The Greek philosopher Plato wrote, "In a single day and night of misfortune...the island of Atlantis disappeared in the depths of the sea." Disney would have it be discovered underneath Iceland…

"I will find Atlantis on my own—if I have to rent a rowboat!" Haha, love that movie!

Wednesday, October 5, 2011

Ancient Greece (pt. 11)

As you can see, these are not cave paintings; these are highly complex murals that took careful designing and paint mixing—the colors today still as bold as if they were applied just a couple years ago. The Minoans had time to develop their art because they had such innovations and were not fighting every day for survival. Since Ancient Egyptian art was primarily for religious purposes, for the pharaoh in the afterlife, it is possible that the Minoans (who came before the Amarna Period) were actually the first to craft art merely for recreation, for beauty, for art's sake. Take a look at this wonderful jar fashioned and painted by Minoan artists.

Frescos like this one lead historians to believe the Minoan culture had their own sporting events before the Greeks introduced the Olympic Games. It shows a game called bull-jumping, which sounds a little dangerous, if you ask me (heehee).

Tuesday, October 4, 2011

Ancient Greece (pt. 10)

Now go back a ways—about a thousand years—to the island of Crete, off the southern tip of the Greek peninsula. (Sorry, I try to avoid anachronistic writing, but there's lots of history, ya know!) Circa 1,700B.C., the Minoan civilization flourished. What's so special about them is that they were probably the most advanced civilization of their time, featuring innovations that would not reappear until the Roman Empire, in the first century A.D. Remnants of the Minoan culture on the island of Crete show us first-hand that these people had such advancements as: two-story houses (where the second floor was in use), toilets, running hot and cold water, vibrantly colorful wall frescos, and stunning gold artifacts made some of the finest goldsmiths of the time—among other things. Furthermore, the people spoke a language totally lost to us and wrote in characters so far unintelligible to us. It is for this reason the Greeks used the word "barbarian" to refer to people like the Minoans—outside cultures whose languages the Greeks did not understand (from the onomatopoeic word "barbar," which means to speak nonsense—"bar, bar, bar, bar"). But these were far from the primitive kinds of people we usually think of when we hear the word "barbarian." In fact, apart from just surpassing the Greeks, the Minoans may have been the single most advanced civilization in the world at that time. Let's have a look at the art…

Thursday, September 29, 2011

Ancient Greece (pt. 9)

It was sculpted to celebrate a naval victory. Nike stands on the prow of a ship, overlooking the island of Samothrace. Wet drapery was a common element in Ancient Greek statues of women; here it's used to relate an image of the goddess standing firm against an oncoming sea wind and sea spray. Her flowing, wet robes give the sense of movement introduced during the Classical Period. This is still considered one of the greatest sculptures in history. Go to the Louvre to see it in person and you will be awed by its grandeur.

Tuesday, September 27, 2011

Ancient Greece (pt. 8)

After the Peloponnesian War, the Hellenistic Period, under Philip II and his son and successor, Alexander the Great (who was taught by Aristotle), switched to a new style. The expression during the Hellenistic Period was emotion and drama. Violent images make their way onto the art scene in order to stir emotion. The beautiful example of this is the Dying Gaul. It is a man from Gaul (France) who has been fatally wounded in battle. Viewers see lots of pain and drama as the man tries to prop himself up and take his final breaths, perhaps contemplating his life and death. Some call the style "emo" sculpture because it is intended to stir emotions in the viewer. You are supposed to feel sorry for this man.

The other tragic Hellenistic figure par excellence is the Seated Boxer. This is a mature, professional boxer resting after a brutal match. He perspires with swollen ears, scratches, a broken nose, battered cheeks, and a joyless expression. It is assumed that, if this pitiful figure has not already been beaten, he will lose the fight. The viewer sympathizes.

Friday, September 23, 2011

Ancient Greece (pt. 7)

Doryphoros's left leg is bent, his toes lightly touching the ground. He is turned slightly, in a relaxed pose, and his head is shifted to the right. The image is an icon of athletic strength and prowess. The Ancient Greeks glorified human strength and athleticism (hence the highly renowned Olympic games). Man is made into a champion, hero, and god.

The contrapposto pose alone, I think, gave the statues more than just a relaxed, "natural" look; it gave the figures an air of confidence and swagger. With this new-found freedom from old rigid forms came a sense of pride. The Riaci Bronze Warriors make for a good example of contrapposto.

These guys were discovered by an Italian man named Stefano Mariotini who was spear fishing on vacation in 1972 when he saw a human arm in the sand (kinda creepy). They were found off the coast of Riaci, in Southern Italy. They resemble human beings but are unrealistic. The legs are too long, and the body is split in half with an exaggerated groove. Their backs are too tense, and their muscle tension is physically impossible. They're also missing a tailbone. The reason for this? The statues were made to look more than human. If it was just a statue of a normal human being it would have been too boring. They exaggerated to enhance the aesthetic experience, and perhaps to enhance their own idea of humanity. These are, so to speak, "more human than human." They are god-like. Why are most Ancient Greek statues nudes (at least those of males)? It was all a part of the admiration of humanity, of the human body, physique, strength, etc. This was the Classical Period.

Thursday, September 22, 2011

Ancient Greece (pt. 6)

Another element of Ancient Greek art was the frieze, which was a decorative band running across the upper part of a wall. The most famous Greek frieze is probably that of the Parthenon. This brilliant frieze shows 350 people and 125 horses in a religious parade that was for a celebration held in Athens every four years. In the frieze, horsemen are bunched up in some places, and strong light and shadow patterns weave themselves throughout the long line of figures. It is an extremely lively work of art, showing incredible amounts of motion among all its figures.

Wednesday, September 21, 2011

Ancient Greece (pt. 5)

Sadly, when the Romans took power, the Greeks' bronze works were melted down, and the marble sculptures were also ruined. The Romans themselves copied much of Greek art. Few surviving Greek statues today are originals; most are Roman copies.

Saturday, September 17, 2011

Ancient Greece (pt. 4)

Greek sculpture is split into three periods: the Archaic, Classical, and Hellenistic Periods. The Archaic Period occurs from about 600 to 480B.C., and it features a great number of kouroi. A kouros was a male youth who may have been either a god or an athlete. They are free standing sculptures of men in stiff, straight poses. They are symmetrically balanced, with the arms and legs separated. Their faces show bulging eyes, a square chin, and a grinning mouth. Both feet are touching the ground, and the only movement is in the left foot. The term for this is contrapposto—a pose in which the weight of the body is balanced on one leg while the other is free and relaxed.

Wednesday, September 14, 2011

Ancient Greece (pt. 3)

Here is the Vase with Ajax and Achilles Playing Morra (dice), painted by Exekias. It shows two Greek generals playing a board game with which they were so preoccupied that they did not hear the enemy coming. Exekias put in details to make the scene realistic, such as the generals' equipment, set aside behind each of them, and he painted it to fit the curve of the vase. By the 6th century B.C. we begin to see artist signatures on pots (the first signed works of art).

Tuesday, September 13, 2011

Ancient Greece (pt. 2)

Greek architecture is one of the staple forms of architecture—arguably the most used style in history. The earliest Greek temples themselves were made of wood or brick, and then eventually builders turned to limestone and marble. The architecture was designed to be aesthetically perfect. The temples were considered to be dwelling places for gods, as Ancient Greek culture centered itself around gods. They built temples as houses for their many gods (who often looked and acted like humans). They prayed at these temples and brought offerings for the different gods. (The Greeks had a lot of gods—remember the "Temple to an Unknown God" in Acts 17?)

There are three Greek orders for temple columns: Doric, Ionic, and Corinthian.

Doric was popular during the 7th century B.C. and featured a plain, simple, basic capital with no base. Ionic came in the following century and introduced a base. Its capital was designed as either a folded scroll or curled ram horns. In the 4th century B.C. came the Corinthian order, which featured an elaborate capital designed as Acanthus leaves.

Construction of the Parthenon began in 447B.C., and it uses Doric columns.

The Romans went on to copy much of Greek architecture, along with several other cultures to come. Early American architecture, like the White House, was heavily influenced by Ancient Greek architecture.

Tuesday, September 6, 2011

Ancient Greece (pt. 1)

Greek history begins around 2,000B.C. (during Egypt's Middle Kingdom). After several wars and invasions, the Dorians took over the land in 1,100B.C., and towns changed into city-states, divided by their geography. As city-states grew in size and influence, rivalry developed, but they eventually united in fear of the Persian invaders during the 5th century B.C. Having successfully protected their land from the Persians, the city-states agreed to combine and form a Delian League in order to prevent more invasions. Athens was made the head of the Delian League.

The prominent leader of the Greeks, Pericles, used money to restore Athens and encourage a period of economic growth and societal peace. In 431B.C., the Peloponnesian War against Pericles started, and the following year Pericles died, along with a third of the population of Athens, from a terrible plague. The Spartans defeated Athens, and a century of conflict followed. In 338B.C., Greece was conquered by Macedonia.

Saturday, August 27, 2011

Ancient Egypt (pt. 14)

In time, the Ancient Egyptians stop constructing pyramids for burial sites. Why? The huge size of the pyramids often acted as a humongous sign to grave robbers that treasures could be found there. The tombs were moved to cliffs like those in the Valley of the Kings. The pyramids were also too expensive and took too long to build, so they were decommissioned.

In 332B.C., Egypt fell to Alexander the Great.

Thursday, August 25, 2011

Ancient Egypt (pt. 13)

Except for the Amarna Period, Ancient Egyptian art maintained the same style for thousands of years (…and that's a long time, considering that art styles later on—like in the 19th and 20th centuries—would change every few decades). Why did the style not change over time?

Archaeologists discovered, painted on a wall on an Ancient Egyptian temple site, red lines that formed a grid. Researchers took that grid and applied it to other Ancient Egyptian murals, finding that the proportions matched each figure identically. The Egyptian artists had been using a grid system to dictate their design of the human body. Like the law-driven society itself, the art was forged through order and consistency. Other grids were found on even more Ancient Egyptian finds, showing that all the drawings had been carefully made with exact measurements and specifications. The grid system was an essential part of Egyptian culture that lasted throughout all three major kingdoms in the civilization's history. It's really quite extraordinary: if you look at images from the Old Kingdom, they will look exactly like the art from the New Kingdom, some three thousand years later—no change. Compared to other civilizations, Ancient Egypt was one of the most static empires in history, and the grid system is one of the evidences for it. Talk about sticking to tradition! (Because artists in the future will come to mock traditional styles and will invent new ones). The Egyptians kept the same style for thousands of years. I marvel at how that could be so, but it's not that easy to look up more about. Sources are few. A good one that I recommend, for more info on the Ancient Egyptian grid system, is the PBS documentary How Art Made the World.

Tuesday, August 23, 2011

Ancient Egypt (pt. 12)

After Akhenaton's death, the art changed back to the way it was before; the prior polytheistic religion was reinstituted; and the capital was moved back to Thebes—the end of the Amarna Period. The god Aton was forgotten, as exemplified with Akhenaton's son, Tutankhaton ("living image of Aton"), whose name was changed to Tutankhamen ("living image of Amun").

King Tutankhamen, successor of Akhenaton, is most famous for his extravagant tomb, which contained more gold treasures than any other Egyptian tomb. The pharaoh alone was buried in seven sarcophagi. The tomb was discovered in 1922 by English archaeologist Howard Carter, who later wrote about the exciting moment of the discovery:

"At first I could see nothing; the hot air escaping from the chamber, causing the candle flame to flicker, but presently, as my eyes grew accustomed to the light, details of the room within emerged slowly from the mist, strange animals, statues and gold—everywhere the glint of gold… I was struck dumb with amazement, and when Lord Carnarvon, unable to stand the suspense any longer, inquired anxiously, 'Can you see anything?' it was all I could do to get out the words: 'Yes, wonderful things.'" – Howard Carter, 1933

Friday, August 19, 2011

Ancient Egypt (pt. 11)

…Ah, is Nefertiti's bust really Realism. I have reason to think it is. Going with the trend of the Amarna Period, it would be, and plus a bust carries the connotation of Realism to begin with (it's the face of the person we're looking at—you know, "the eyes are windows to the soul"; a bust is perhaps the closest we can come artistically to "viewing" someone's soul…I guess until we get to Expressionism, but we're a long way's away from that!) The sculptor certainly does show her as a beautiful queen, and so it could be a Romanticized image of her. It could be, but we don't know, because this is the only image we have of Nefertiti. Her tomb was raided after her death, and her mummified face was smashed to keep her from going to the afterlife.

Thursday, August 18, 2011

Ancient Egypt (pt. 10)

Another is this very famous work of art, the bust of Nefertiti.

The first shocking quality: it is a statue of just a woman, and no man. Womankind, made from man, the weaker vessel, "the serpent's prey," submissive to her husband, and in every way lower than men during that time, is here elevated to such a level of importance that a statue is made solely of her—alone, independent. The next thing to shock me is: the statue is a bust (which is the name for a statue of only the shoulders up on a person). Remember the Venus of Willendorf—that supposedly, women in ancient times were only good for childbearing and keeping the race alive (or, in the case of the Egyptian pharaohs, providing heirs to keep the dynasty enthroned). Well, here there is no attention whatsoever given to female reproductive organs; it is just a bust of her face. And a proud-looking face it is, furthermore, is it not? Her head is held up high, not quite like a submissive wife's. (And the name Nefertiti means "the perfect one"). It is the face of a person that most expresses his/her character, personality, emotions, etc. Here, although she is the queen of an empire and the wife of a pharaoh, the sculptor just shows us Nefertiti's face—Nefertiti as she is, as a person. Enter Realism. Now say goodbye, because we won't see this again until the Romans.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)