The French art movement that

immediately followed Impressionism still regarded light and its effects on

color; in addition, the most influential artists of this developing

Post-Impressionist style, such as Paul Cézanne, Vincent Van Gogh, and Paul

Gauguin, wanted more intense color and stronger forms. This is the type of art we see during the

late 1880s and 1890s in Paris—and Paris was the art center of the world. In continuation of the artistic theories of

Impressionism and then of the preceding generation, we begin this period with a

look at the works of Paul Cézanne.

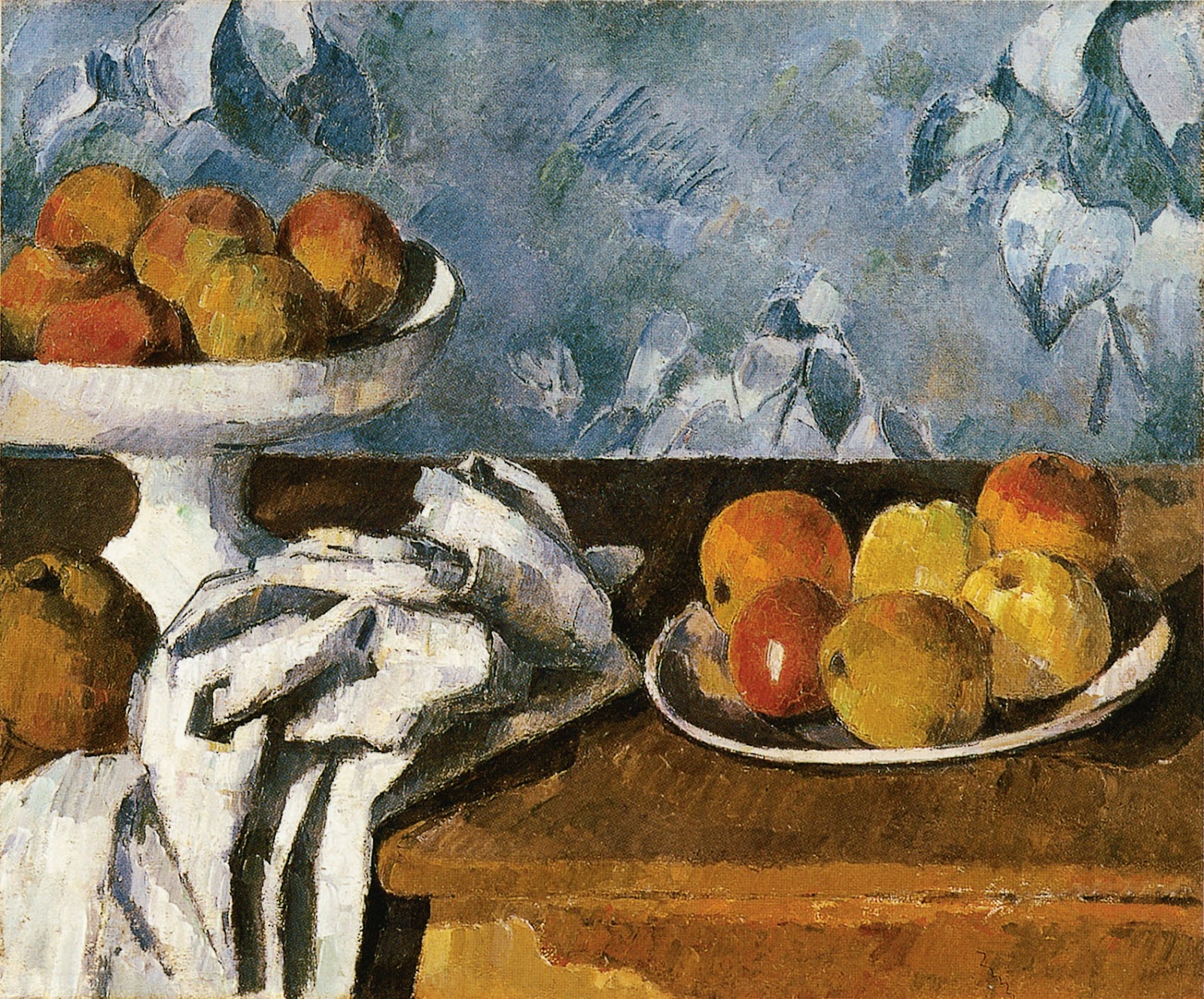

Cézanne believed that Impressionist

paintings lacked form, solidity, and structure.

The wispiness of their brushstrokes did not definitively convey an

object as the chosen center of focus, and the scenic layout of their works

threw away a convention which Cézanne thought necessary to keep for art's sake:

structured order and strategic placement of objects (like a still life). His goal was to make "something solid,

like the art of museums." So he

painted arranged objects, rather than painting them as he found them. This approach was not too realistic, then,

but Cézanne did not mind constructing a fake structure around the image so as

to better depict the object. He

discarded anything that he felt was unnecessary.

In this still life painting, he has

arranged four skulls in a pyramid-like fashion, not as they would naturally

appear in the real world. He has moved

them onto a tabletop or some other surface (the artist doesn't delineate) and

intentionally placed them in this construction, a fake layout, quite different

from the candid images of Impressionist art.

The Impressionists sought to make observations about the natural world

through art, so artists like Renoir and Monet painted scenes as their eye saw

them, not always containing formatted structure or clarity. Cézanne's art took greater liberties with

rearrangement and alterations from the natural forms of objects in order to

better narrow in on the painter's own objective, which, in Cézanne's case, was

to focus on depicting the object itself.

The circumstances around the object and the object's own placement

within an environment didn't matter—after all, this was art.

This is why his early still life

paintings don't look realistic. The

artist was willing to sacrifice realism in order for certain objects to appear

solid and heavy. It was part of his

devotion to the object; that it had to be depicted in as comprehensive a manner

as possible for art. And arguably the

most daunting aspect of any object when contextualized in a painting is its

mass and three-dimensionality. So

Cézanne would brush up his canvases with thick strokes of paint to convey the

thickness of an object's volume. Up

close, this style appears flat, but when you stand back the items in these

paintings take on a solid, semi-3D form.

This technique better delves into the nature of the object, as opposed

to the effects of light or atmosphere on the object's appearance, and therefore

(theoretically) gives a better impression of that object's true essence.

No comments:

Post a Comment